Krystal DiFronzo’s installations of painted sheets and banners deal with pharmakon and the grey areas between medicine, poison, desire, illness, and its effect on femme bodies and labor through exploitation and myth. She holds a BFA from SAIC and an MFA in painting from Yale. She recently relocated from New Haven, CT, to Ridgewood, NJ. Krystal’s most recent installation, Messengers and Promises, graced the Dirt Palace window in the month of August. I had the privilege to ask about the installation, her process, and the many mining grounds in her work. Messengers and Promises

“Animals first entered the imagination as messengers and promises.”- John Berger

Time has proven to be a difficult thing to grasp in quarantine. The only moments it has felt concrete has been in observing the slow cycles of growth and death of plants and insects that I witness on daily hikes through East Rock park here in New Haven. Or on drives looking at roadsides in the height of New England summer at the towering mullein, the paper crepe blossoms of chicory, fanning Queen Anne’s lace and the already seeded dandelions cracking through pebble and gravel and thriving off exhaust. Feeling thrilled by these resilient weeds full of nutrients and medicinal properties, emerging on the fringes of construction sites, despite efforts to eradicate them. Similarly thinking about the beast of burden, like the donkey in Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar. Its relationship with humans ranging from being lovingly adorned with flowers at one moment and tail lit aflame at another yet continuing on, only able to convey its anguish in a cry. Researching how butterflies feed off of rotting fish and dung for essential nitrogen and other minerals. Trying to find some solace, or a key in these means of survival, growth and endurance in an ever more toxic environment. Looking to the ass’s bray in its refusal to perform labor as a form of protest.

Keegan Bonds-Harmon: Your work is incredibly immersive. The worlds you are building in your studio are dense with references to the occult, pharmacological, and mythological. I'm curious to hear about how you first fell down this rabbit hole. Do you have any early memories that feel significant to your work today? Or more recent experiences that drew you into your subjects?

Krystal DiFronzo: I think a lot of my early instincts with storytelling and my interest in mythical world building has been a need to explain indescribable emotion or phenomena. The most influential things that framed this type of magical thinking early on were movies like The Rats of NIMH, children’s encyclopedias on world mythology, and the saint iconography that was always sort of in the background in my Italian Roman Catholic family. I was an extremely sensitive kid and images like St. Sebastian strapped to a tree and pierced with arrows spoke so true to me. I saw not only pain but radical vulnerability as a way to communicate on another level. It’s a continuous hunt for icons, images, and histories that connect to my current lived experience or that I feel relate to each other in unexpected narratives.

KBH: How did you come to your materials? What drew you to these transparent silks and natural dyes? And what's your secret to maintaining such delicacy and grace?

KD: My current exploration of natural dyes was born last summer when I was working as staff at this undergraduate art residency run by Yale in the Berkshires. I had been painting large banner-like pieces on muslin with washes of Jacquard cold water dye because the bleed shook me out of my tendency for tight linework. I spent a day with one of the co-directors, Byron Kim (who has been painting with natural dyes for quite a bit), dyeing with gardenia, indigo and cochineal. I was doing a lot of work about bodies returning to soil and being in that wooded environment surrounded by rotting leaves, insects, and fungus put that more into focus. This processing of organic matter clicked with me as a way of finally connecting the physical material used to the work that felt fully intentional. I'm also a little bit of a control freak and the uncertainty of these dye processes adds a bit of chaos, chance and magic to the equation. I grew to love working with silk for its strength and transparency. There is also something so satisfying about drawing with resist. After the work is steamed you wash it out and the image literally becomes embedded into the material, not merely sitting on the surface. The secret is that silk is an unreal fiber with a life of its own, it does most of the work!

KBH: On the left hand wall of your installation Messengers and Promises at The Dirt Palace was a banner that read “Fools can enter where angels fear to tread”, an idiom from an Alexander Pope poem which is often referenced in music. Could you tell me about your relation to these words?

KD: I actually got to that line from an essay in a Marina Warner book called From the Beast to the Blonde where she explores the roles of certain archetypes in fairy tales. The essay is on the work of Angela Carter. The full quote is : ”The Fool in Dutch painting deals in comic obscenity in this manner: as fools can enter where angels fear to tread, and thumb their noses (or show their bottoms) at convention and authority tomfoolery includes iconoclasm, disrespect, subversion.” I was thinking about the resourcefulness and scrap of the Fool, sort of transcendence through laughing in the face of the oppressor.

KBH: After reading your statement for Messengers and Promises I watched Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar, a film you cite as an inspiration to the installation. The movie follows the story of a donkey named Balthazar, and his shifting owners. Balthazar is cared for lovingly, baptised by children, abused by farmers and misfits, and made to perform tricks in a circus. Balthazar’s life parallels that of the main character, Marie, and becomes a symbol of perseverance and burden. How did you connect with this movie? What does the donkey symbolize for you in this work?

KD: I think I saw Balthazar for the first time probably around your age as well. Since then it has always got me straight to the gut. I’m sure it has something to do with my embedded Catholic guilt, labor and toil as cleansing of sin. Then, yes, there’s the beauty of resilience! I came back to this film because an essay in the same Marina Warner text sparked something. In it she describes the donkey’s bray as “ (it) speaks for the passion of the creature without language… In spite of the loudness and persistence of its cry, it is an animal that can not communicate: the very intensity of the bray conveys that condition of powerlessness, of exile from human congress.” I feel like the donkey becomes this icon of empathy and the effect imposed labor has on a body, a beast of burden that protests but continues on regardless.

More Weight, 2019

KBH: You cite bodily experience as a mining ground for your work. In your statements you mention the boundaries between bodies and their environments, Thomasine Younger’s failed tooth surgery performed by a town cobbler, and your own experience in chemotherapy. Through transparency the figures in your tapestries are diffused into what feel like layers of mist. They float in space like apparitions. Could you speak on the tension between these very physical and ethereal aspects of your work?

KD: Those projects in particular ( Dogtown, No Shelter and More Weight) use transparency as a way to layer histories like ghostly sediment. Then I use writing, drawing, or objects like literal rocks to reground it into the physical and present. It’s that tension between the histories in the ground under your feet that reflect your own bodily experience in strange ways that I’m striving towards. Like how the specific mold used in one of my chemotherapy drugs was discovered in the ground mere minutes from where my grandfather grew up in the Apulia region of Italy.

Dogtown, No Shelter (2019)

KBH: Your installations tend to imply a story: a resistant donkey, an owl on a mission, a tormented witch. I saw that you have a background in comic and zine making. How do you navigate storytelling in your work? What role does it play for you and how do you consider the audience's read of a zine as opposed to that of an installation?

KD: I fell in love with comics because of the visual framework embedded in them. The toed line between what can be expressed in writing and what can only be expressed visually, as well as how time and thoughts are marked. I definitely see the influence of that in everything I make. The installations become an exploded version of the straight linear story. Space becomes a tool to manipulate the interpretation of the narrative as well as time. The space of the shop window at Dirt Palace for Messengers and Promises became a single scene or panel while in a work like Divine Lady Owl the space between banners of individual images acts more the gutter in a comic but the direction of time and meaning of the narrative becomes complicated because the viewer experiences the work in the round and has to come to their own conclusions as to their relationship with each other. This is where meaning gets exciting and complicated, I’m less and less interested in feeding a direct narrative.

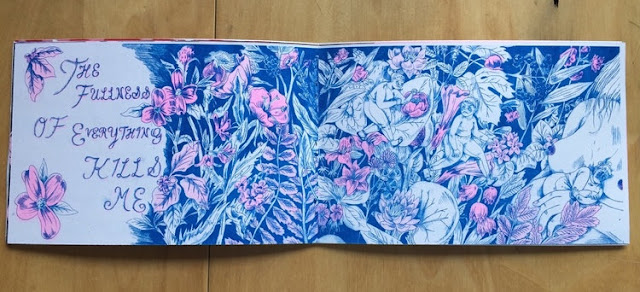

Homo Sapiens Non Urinat In Ventum, 22 pg. two-color risograph zine 2015

KBH: You recently graduated with an MFA from Yale in the midst of lock down, its dismemberment of our physical spaces, and our rapid and clumsy efforts reconstruct a semblance of normalcy. Has this experience left you with any new visions for a stronger reconstruction of arts' spaces, educations, or roles in our communities?

KD: Woof! Yeah. It’s been a pretty rattling experience. Going through two months of online courses and critiques has been mostly upsetting and nerve wracking. I was on track to be teaching next Spring and thankfully can put that on hold right now because I honestly feel so uncertain about the role of higher education at the moment. I’m not shocked but so disappointed by the lack of support these institutions with huge endowments (that feed off predatory loans, investments in fossil fuels etc., underpaid admin staff and adjunct faculty) have given. What this has done, and I think a lot of people have had similar experiences in other fields, is it’s highlighted the importance of the immediate and local. The most faith I’ve had in education recently was living at Yale Norfolk and working directly and openly with students in a sort of dual role as mentor and peer. I also recently moved to Ridgewood, Queens to be back with a community of peers I worked with in DIY spaces in Chicago and having that support again feels vital with so much uncertainty. I’m a big believer that things like mutual aid and unique accessible forms of education will be a saving grace in the months to come.

KBH: Do you listen to things while you work? Do you have any music, audio books, or background-sound kind of shows you would recommend to any of the artists reading at home? Or do you prefer a quiet studio

KD: When I’m in research and writing mode I can’t do sound and usually cycle between walks and going back to the studio. When I’m in the groove of like weaving or drawing I switch between podcasts and music. I’m an October Libra and this is my favorite time of the year so I’m really leaning into heavy spookiness. The late Geneviève Castree’s projects Woelv and Ô Paon are hugely important to me and I’ve been revisiting those as well as getting into Chrysia Cabral’s Spellling and the excellent Oakland doom metal band Ragana. Also Kate Bush forever and always.

L: An Unformed Venus, 2019, Ink on paper (55 in x 42 in) R: A Rattlesnake Rotting In Your Well, 2019 Ink on paper (55 in x 42 in)

KBH: In your work I see a push and pull between forces of good and evil. Deities and demons, flowers and venomous insects, medicines and toxins. In your statement for Messengers and Promises you describe butterflies who feed off dung and fish carcasses for nutrients. Is there anything you are doing inside or outside the studio to metabolize the world around you, to maintain balance, or to alchemize an antidote to the psychic morass that is the mid-covid-landscape?

KD: Honestly, for the first time in my adult life I have a car and that level of freedom has been keeping me going. To be able to take drives through Long Island, Upstate, and New England. Getting my feet elsewhere, breathing a different type of air, witnessing something physically new and processing that as opposed to the BIG PICTURE things we are all attempting to process helps me feel grounded. A big fan of forest bathing and salt water! Also reading up on plants as I hike and visiting one site multiple times through a season has been hugely balancing.